Dead Air: The Ruins of WFBR Radio

Posted: 07th August 2017

In: Blog

This crumbling stairwell lead up into the remains of WFBR Radio.

The building that formerly housed WFBR Radio in Baltimore has had many lives and uses, and pulling apart the history of when one ended and another began can be a bit of a challenge. According to a terrific article by Brennen Jensen on Baltimore Heritage it was originally a car dealership and bi-level garage built in 1913 - a fancy one, too, as "part of the second floor housed a chauffeur’s lounge, replete with smoking room and billiard tables." Owners and brands changed throughout the years.

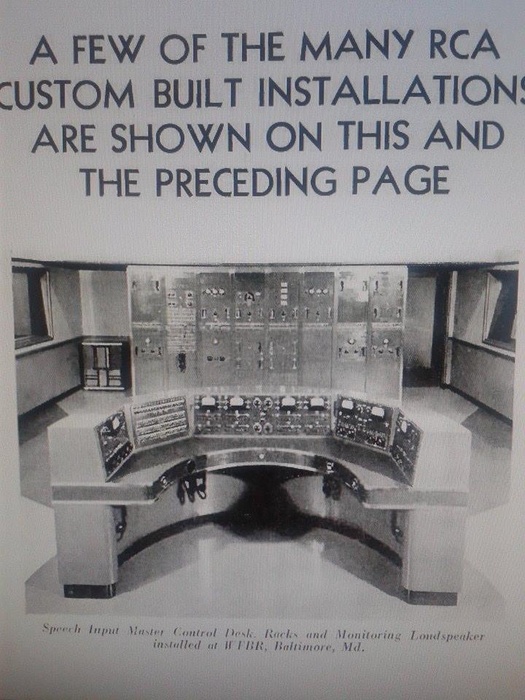

Described as "state of the art for the 1940s" by a former worker, this custom console routed audio from all three studios.

Ad advertisement for the console pictured above when it was new.

The records room, sans records.

WFBR, or "World's First Broadcasting Regiment", was Maryland's first broadcast radio station and was founded in the 1920s on the 1300 kHZ signal by the "officer's association of the 5th Regiment, Maryland, in whose Armory on Preston St. it broadcast from," according to Wikipedia. It's unclear when WFBR moved to the second floor of the 10 E. North Avenue building, but it's probable that it was at the same time the 1,000 seat, climate controlled Centre Theatre opened in the building in 1939. Cinema Treasures reports that "It was the first theatre in the city equipped for radio broadcasting in-house (other theatres had broadcast via remote before) and the first with the ability to project live television on the screen." The theater's Art Moderne auditorium, fittingly compared by Jensen to a Bakelite radio, was a marvel of elegant design and won Baltimore's architectural blue ribbon. It is long gone, destroyed after it closed in 1959 by the Equitable Trust Company in the process of converting the first floor into a check processing center. While it's said that some traces of the theater's lobby remained, I certainly wasn't able to find any while I was there.

The Centre Theatre, circa 1939.

In 1987 WFBR's star shock-jock DJ Johnny Walker left and the station lost the rights to broadcast Orioles games to a rival. It was sold the following year to Infinity Broadcasting, who fired all the on-air staff and switched to an oldies format. They moved to a newer facility and shortly after changed the station's famous call letters. The station would change formats and letters again several times until winding up at WJZ, an ESPN affiliate. With the change, WFBR was dead, although the call letters were later resurrected by a small station in Glen Burnie broadcasting at 1590 kHZ. Meanwhile, at some point (I can't find details on when) Equitable Trust floundered and was replaced by a church that operated on the first floor until roughly 2008. After they went under, everything was left to rot.

There must have been a point when these orange sectional seats seemed like a good idea.

The building as I entered it in November of 2013 was a dark, disorienting mess. Plants grew out of the stairwell leading up to the radio station, and the walls were a mixture of drooping wallpaper, crumbling drywall exposing the brick underneath, and mold. I began on the second floor in the pitch black heart of the radio station, and worked my way out through a maze of rooms that no longer had any clear indicators of their original use. Ratty orange sectional seats were littered about with dozens of other chairs in one room; in another the ceiling had caved in and sunlight poured in through a hole rimmed by rotten insulation. The door to the bathroom fell apart as I opened it, and the metal panes that had held up the drywall in areas were dangling at eye level, more like rusty spears than anything. As with many abandoned spaces, odd mysteries were presented by the space: why was one hallway filled with piles of fake flowers? Who left the collection of bikes and bike tires in the moldy green room, and why?

Why are there so many fake flowers in this hall? The world will never know.

"Who left you here, bike tires?" I asked, but the old tires kept their secrets.

The first floor, where the church had once been operating, was less of an enigma and more like something out of a half-forgotten nightmare. No windows meant no light - but it also meant that all the rainwater coming in through the roof over the second floor was trapped. The thin shaft of light from my flashlight never seemed to illuminate enough, and nearly every surface was being consumed by mold. Everything was damp, ceiling tiles had fallen and lay on the floor like filthy sponges, and cheap book cases slouched over onto desks as their veneers warped and the pressed wood beneath melted. While normally I despite using any sort of flash to alter natural lighting, there was no other option here. The strobe flickered for a split second, casting long, harsh shadows across an eerie environment being devoured by toxic fungus, and then left me in the darkness again with no time to process what I had just seen save via the LCD screen on the back of my camera. I am not superstitious, but it's easy for your mind to play tricks on you or misinterpret what you're seeing in such an unnatural place. With your senses on red alert already, any odd sound or moving shadow seems ominous, particularly somewhere that looks like the physical embodiment of an architectural disease. I don't particularly enjoy locations where there is absolutely no light or ones with high mold concentrations, and usually the first leads to the second.

Pictured above: Not a healthful environment.

It appears that this bookshelf is trying to eat this projector and desk.

Thankfully the visit was uneventful. I was somewhat disappointed not to find any remnants of the building's days as a theater or car showroom, although perhaps I did but didn't recognize them. The same year that I visited, Jubilee Baltimore acquired the building and began a $19 million project to rehabilitate it. According to their website "[t]he Centre is now home to the film programs of Johns Hopkins University and Maryland Institute College of Art, The Baltimore Jewelry Center, Sparkypants Studios, The Impact Hub and The Center for Neighborhoods, a collaborative work space for nonprofits that serve Baltimore neighborhoods." It's a terrific reuse project that maintains the character of the building's exterior while updating the frankly rather uninspired ruins inside into a contemporary artspace. As with the Lebow Brothers Clothing Company, Baltimore has successfully turned another blighted property into a vibrant part of the community fabric once again without destroying what made them unique. I like blighted properties, but I would definitely consider this a victory.

I'm assuming the new building does not have as many plants growing from staircase walls, though.

There are many more images from this location in the full gallery here. For more information on Matthew Christopher's Abandoned America's book series visit this info page or Amazon. Photographs and unattributed text by Matthew Christopher. For more images click the thumbnails below.

Comments

By Emily Hester: Love to hear that the building was able to be saved. Where I'm from two bulgings are said to be unsound and must be torn down. This will forever change the look and feel of our historic downtown.

By Emily Hester: Love to hear that the building was able to be saved. Where I'm from two bulgings are said to be unsound and must be torn down. This will forever change the look and feel of our historic downtown. By Ken Stuart: do you have any shots of the transmitter. Would greatly appreciate getting some if you do. Thanx - Ken

By Ken Stuart: do you have any shots of the transmitter. Would greatly appreciate getting some if you do. Thanx - Ken By Edward Bishop: The size of the 'records room' looks deceptively small; I'd bet up to 5K in Lp's and who knows how many 45's could have been stored there.

Agreed on the transmitter, though that might have (alas) been torn down after the radio station went under.

By Edward Bishop: The size of the 'records room' looks deceptively small; I'd bet up to 5K in Lp's and who knows how many 45's could have been stored there.

Agreed on the transmitter, though that might have (alas) been torn down after the radio station went under. By Gallagher: Anyone know of what happened to Johnnie Walker? After WFBR had a great bar for a time, then what? Anyone know? At time was a great guy, I thought.

By Gallagher: Anyone know of what happened to Johnnie Walker? After WFBR had a great bar for a time, then what? Anyone know? At time was a great guy, I thought. By Doug Douglass: Is there a street address for the building?

By Doug Douglass: Is there a street address for the building? By Raelene Kilichowski: Has anyone that previously worked at the radio station ever contacted you? Would live to hear their take on these amazing photos! Great work!!

By Raelene Kilichowski: Has anyone that previously worked at the radio station ever contacted you? Would live to hear their take on these amazing photos! Great work!! By John Snow: Amazing photos and ruins! It's grand that they are "resurrecting" this old gem. We had an elegant Centre Theater in SLC utah until it was absorbed by a high-rise office tower. Now a mega-screen with none of the old soul of the original. Thank You for sharing these old pics with me.

By John Snow: Amazing photos and ruins! It's grand that they are "resurrecting" this old gem. We had an elegant Centre Theater in SLC utah until it was absorbed by a high-rise office tower. Now a mega-screen with none of the old soul of the original. Thank You for sharing these old pics with me. By Ed Blake: There is a Johnnie Walker that is a DJ on Elvis radio on Sirusxm

Great show in Lancaster thanks for juring me in

By Ed Blake: There is a Johnnie Walker that is a DJ on Elvis radio on Sirusxm

Great show in Lancaster thanks for juring me in By Adrienne: I worked there in the late seventies until the early eighties. I remember that board

By Adrienne: I worked there in the late seventies until the early eighties. I remember that board By Esther Sanchez: I, like the explanation this pictures give of the negligence that can be accomplish with out the proper supervision, it would be nice that somebody did something worthwhile fast would you be able to follow up on that also? some of this places are very far away to be able to have some body to fix them , well considering that you got there it would mean others could also get there. Good work

By Esther Sanchez: I, like the explanation this pictures give of the negligence that can be accomplish with out the proper supervision, it would be nice that somebody did something worthwhile fast would you be able to follow up on that also? some of this places are very far away to be able to have some body to fix them , well considering that you got there it would mean others could also get there. Good work By Chris Bergelt: Really great pictures. Nice to see this abandoned radio station. Keep it up guys.

By Chris Bergelt: Really great pictures. Nice to see this abandoned radio station. Keep it up guys. By Patrick Byrne: I recall the “Walnut Award of the week” that Walker did each week to a deserving soul.

By Patrick Byrne: I recall the “Walnut Award of the week” that Walker did each week to a deserving soul. By Megan Latham: I am from Glen Burnie MD and have always wondered about that small radio station building just a walk up 8th ave from my house. What a marvelous history and gallery of WFBR and the mention of an old-timer I used to listen to w/ my grandpa. I am enjoying your website very much.

By Megan Latham: I am from Glen Burnie MD and have always wondered about that small radio station building just a walk up 8th ave from my house. What a marvelous history and gallery of WFBR and the mention of an old-timer I used to listen to w/ my grandpa. I am enjoying your website very much. By Irene Conn Mitchell: I sang at WFBR in 19939 and 1940 on the Carnival of Fun Show with the all girl Show was written by Brent Guntschorus.

By Irene Conn Mitchell: I sang at WFBR in 19939 and 1940 on the Carnival of Fun Show with the all girl Show was written by Brent Guntschorus.