One regular complaint we receive from listeners is that our podcasts are too quiet to hear properly in noisy environments, such as in cars or on trains. We've spent some time working out what we could do to improve this and from today we will begin to apply loudness normalisation processing to the BBC’s audio clips and podcasts. At this time we are not applying any processing to live radio streams or full programmes made available on-demand.

Applying loudness normalisation will improve audibility for listeners in noisy environments, whilst also reducing the loudness differences between the many services and types of content that the BBC produces.

Why are some podcasts quiet?

Audio can take a number of routes to get online. Some routes may have audio processing applied and other routes may not. This means a live stream from Radio 1 with audio processing applied may be much louder than a podcast from Radio 4 which comes to us direct from the studio.

While the live stream from Radio 1 might be loud enough for the train, there is a good chance the quiet sections of the Radio 4 podcast will be harder to discern in the same environment. As portable music players have limits to how loud they can go, it might not be possible for a listener to turn the volume up enough in those conditions. Also, as increased personalisation allows us to offer listeners programmes on subjects of interest to them from different networks, for example jazz programmes from Radio Scotland and Radio 3, those differences in loudness between programmes could force listeners to reach for the volume control more often than they want to.

Loudness versus levels

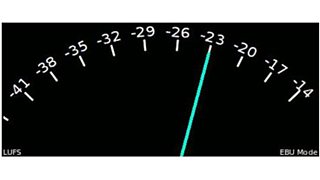

One fairly recent change in audio processing has been the introduction of loudness based measurement. Loudness measurement takes account of the human ear’s increased sensitivity to certain frequencies and introduces a weighting to allow for this (K weighting). For a better understanding, please see this previous internet blog.

For a good technical explanation of the different level and loudness measurement scales, please see this BBC R&D white paper.

When we process audio for loudness, there are three main values that we consider:

1. The overall loudness of the entire programme or clip. This is called the “Integrated Loudness” and is measured in LUFS (Loudness units, full scale). Hence the “All you need is LUFS” badges worn by audio engineers.

2. The “Loudness range (LRA)” (measured in Loudness units, LU). The bigger the value, the greater the dynamic range available between the quietest and loudest moments.

3. The loudest peaks of the programme need to be controlled. Peak values are measured in dBTP (decibels, True Peak) and need to be below 0 dBTP to prevent a type of audible distortion known as clipping.

All you need is LUFS

The current broadcast standards for loudness are based around the ITU-1770 measurement recommendation, and the EBU R-128 recommendation which specifies a target integrated loudness of -23LUFS. This value works really well in the home and is the standard for our HD television transmission, but when a programme recorded to an integrated loudness value of -23 LUFS is played in a noisy environment on portable equipment with its legal volume limits, it can sound very quiet compared to commercial music, and at worst it can become inaudible against the background conditions.

The BBC has been contributing to a new loudness recommendation aimed at online streaming, which takes account of the need to compensate for these factors. This was published as AES (Audio Engineering Society) recommendation 1004.

Bearing these recommendations in mind, we have decided to normalise our podcasts and audio clips to the following values.

• Integrated Loudness: -18 LUFS

• Loudness Range: 13 LU

• Maximum true peak level: -2dBTP

These values are a bit of a compromise. If we were just processing speech, we might go for a greater reduction in the loudness range, just pop music, we might look for higher integrated loudness values. As we will be dealing with everything from drama and classical music to electronic dance music, we chose values that would improve audibility while not impacting too heavily on the programme makers' original intent, allowing room for dynamics and not trimming too many peaks. We are trying to remain as transparent as possible to the listener.

If this work proves successful for podcasts we may apply it to all radio programming. If we do that, we will be able to use a range of target values so that we can tailor processing to the network’s content as we do for broadcast, while keeping our output within a manageable range of values.

Hopefully, in the future we will be able to add loudness metadata to our streams so that players can use the values to provide their own compensation, possibly taking into account the ambient noise levels through the built in microphone on mobile phones for example.

This is a first iteration of loudness processing and we’ve thought about the target values carefully, bearing in mind the amazingly wide range of content BBC radio produces and also what others are doing, not least the range of different values being proposed by the makers of voice activated speakers! We look forward to your feedback on the changes so that we can make adjustments if necessary to keep improving the listening experience.